Turning Point for Hope on Climate Action?

Veteran activist Bill McKibben lays out the case for cautious optimism

AfricaFocus Notes on Substack offers short comments and links to news, analysis, and progressive advocacy on African and global issues, building on the legacy of over 25 years of publication as an email and web publication archived at http://www.africafocus.org. It is edited by William Minter. Posts are sent out by email once or twice a month. If you are not already a subscriber, you can subscribe for free by clicking on the button below. More frequent short notes are available at https://africafocus.substack.com/notes, and are also available in an RSS feed.

Editor’s Note

Social movements, such as the anti-apartheid and Southern Africa solidarity movements of the second half of the 20th century, require decades of organizing work. And the pace of progress (or setbacks) is uneven. But at times the potential for breakthroughs changes rapidly. Listen to the Wisconsin Public Radio panel below for reflections on the connection between Southern Africa solidarity and solidarity with Palestine today, with particular reference to Madison, Wisconsin.

Veteran climate activist Bill McKibben recently argued in a long Substack post that now may be such a time for the climate. I have reposted excerpts below, as well as a link to the full article.

For additional links to recent articles on climate change that I have also found helpful, visit this spreadsheet.

Wisconsin Public Radio Panel

Last month I participated in a 20-minute panel on Wisconsin Public Radio on the links between anti-apartheid protests in the 1960s and 1970s and the Palestine solidarity protests this year. The other panelists were my long-time friend and comrade Prexy Nesbitt and University of Wisconsin sociology professor Gay Seidman.

An article by WPR producer Tim Peterson about the panel is here:

And the audio is available at this link:

What You Want is an S Curve

And we're finally hitting the sweet spot of the crucial one

Bill McKibben, June 11, 2024

[Excerpts: For full article click here.]

Regular readers of this column know that I think we’re engaged in the most desperate race in human history—a race between a rapidly unraveling climate, and a rapid buildout of renewable energy. The outcome of that race will determine just how many people die, how many cities drown, how many species survive. Pretty much everything else—efforts to restore corals, say, or worries about how exactly we’ll power long-haul aircraft—is noise at the margins; the decisive question is how those two curves, of destruction and construction, will cross. Oh, and the relevant time frame is the next half-decade, the last five or six “crucial years.”

So even amidst all the desperate news from climate science, I have some legitimately good numbers to update you on this morning. They come from the veteran energy analyst Kingsmill Bond and colleagues at the Rocky Mountain Institute, and they demonstrate that the world has moved on to the steep part of the S curve, which will sweep us from minimal reliance on renewable energy to—we must hope and pray— minimal dependence on fossil fuel.

…

It seems pretty clear, according to Bond’s team, that last year or this we will hit peak fossil fuel demand on this planet—the advent of cheap solar and wind and batteries, combined with rapidly developing technologies like heat pumps and EVs, has finally caught up with the surging human demand for energy even as more Asian economies enter periods of rapid growth: the question is whether we’ll plateau out at current levels of fossil fuel use for a decade or more, or whether we can make fossil fuel use decline enough to begin to matter to the atmosphere.

And the numbers in the new report give at least some reason for hope: sun and wind are now growing faster than any other energy sources in history, and they are coming online faster that anyone had predicted, even in the last few years. In the last decade, “solar generation has grown 12 times, battery storage by 180 times, and EV sales by 100 times.”

…

Solar power in particular is about to become the most common way to produce electricity on this planet, and batteries will this year pass pumped-hydro as the biggest source of energy storage; the supply chain seems to be in place to continue this kind of hectic growth, as there are enough factories under construction to produce the stuff we need, and investment capital is increasingly underwriting cleantech (though a treacherously large supply of money continues to flow to fossil fuels). Pick your metric—the number of cleantech patents, the energy density of batteries, the size of wind turbine rotors—and we’re seeing rapid and continuing progress; the price of solar power is expected to drop by half again in the course of the decade, reinforcing all these trends. The adoption curves for cleantech look like the adoption curves for color tv, or cellphones—that is to say, from nothing to ubiquitous in a matter of years.

A big reason for the ongoing change—and for ongoing optimism—is the simple efficiency of the technologies now ascendant. A second report from Bond’s Rocky Mountain Institute, this one published last week, focused on these numbers, and they’re equally astounding. By their calculations, we waste more than half of the energy we use.

…

We’ve invested mostly in increasing the volume of energy we use, not its efficiency—because that was what made big money for Big Oil. But cleantech is inherently more efficient: when you burn fossil fuel to make power, you lose two-thirds of the power to heat, which simply doesn’t happen with wind and sun. An EV translates 80-90% of the power it uses into propulsion, compared with well less than half for a car that runs on gas. A gas boiler is 85 percent efficient, which isn’t bad—but a heat pump is 300% efficient, because its main “fuel source” is the ambient heat of the atmosphere, which it translates into heating and cooling for your home. That means that the higher upfront costs of these technologies quickly translate into serious savings. And these kind of numbers bend curves fast.

…

Just to give an example, the EV maker Rivian—which only produced its first models three years ago—last week announced a redesign, which will remove 1.6 miles of wiring from each vehicle. That’s among other things a lot less copper—and indeed the price of copper has remained relatively stable even as electrification proceeds.

2030 is, I’ve long thought, the relevant deadline. And so back to that IEA report, which gives us the play by play on the race.

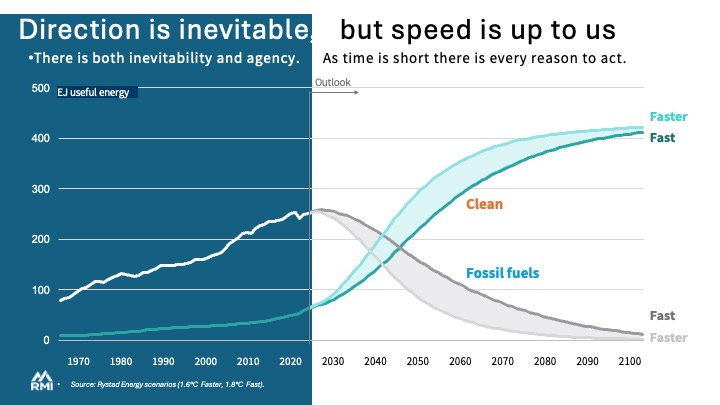

Here’s a graphic representation from the RMI study, and it’s worth scrutinizing. The difference between ‘fast’ and ‘faster’ is what I’ve been describing—the shaded areas between them may well be the most important shade on an ever-warmer earth.

+Tasneem Essop, the remarkable head of Climate Action Network International, and Elizabeth Bast of Oil Change International, argue persuasively that it’s time for an actual and serious transfer of funds from the countries that have gotten rich damaging the climate to the countries in desperate need of clean energy

Rather than relying on the private sector, rich countries can afford the grants and highly concessional finance required for a fast, fair and full phase-out of fossil fuels, which societies and communities want. There is no shortage of public money available to fund climate action at home and abroad. Rather, a lot of it is currently going to the wrong things, like dirty fossil fuels, wars and the super-rich.

The lack of progress is also a symptom of a larger global financial system where a handful of Global North governments and corporations have near-full control. This unjust architecture results in a net $2 trillion a year outflow from low-income countries to high-income countries, historic levels of inequality and food insecurity, and record profits for oil and gas companies.

To raise the funds, wealthy governments can start by cutting off the flow of public money to fossil fuels and making polluters pay. The science is clear that there is no room for any new investments in oil, gas or coal infrastructure if we want to secure a liveable planet. And yet governments continue to pour more fuel on the fire, using public money to fund continued fossil fuel expansion to the tune of $1.7 trillion in 2022.

…

In 2023, as per independent fund investment research house Morningstar, sustainable funds had a median return of 12.6% versus 8.6% for traditional funds. This outperformance extended across equity and fixed-income funds asset classes.

Europe, the most advanced regionally in embracing sustainable funds, saw an inflow of almost US$11 billion into this asset class in the quarter ended March 2024. In contrast, ESG investing appears politicized in the United States and is seeing outflows.