Reading Africa and World History

From Central Gondwana to Global Apartheid

We are all descended from African ancestors, whether we now live on the continent or someplace else in the world. This common ancestry is now widely recognized, as summarized in this nicely done 2-minute video (mute the sound to avoid the schmaltzy music).

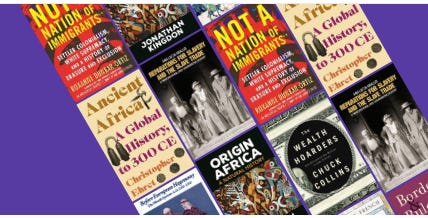

But that history is extraordinarily complex. New dimensions over longer time periods are being explored by scholars making use of both new and old research tools. This AfricaFocus post is a selected reading list of books that I have found of interest, almost all published recently, which I have read or am now reading. All cover a wide canvas rather than focusing on specific times and places.

Note: The links on the titles are to Bookshop.org. All except the book by Janet Abu-Lughod are also available on Kindle.

Part I: Ancient Africa

Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE (June 2023) is the latest book by Christopher Ehret, who has pioneered the use of linguistic, genetic and archaeological evidence to untangle history beginning more than ten millennia before the present. Notably he shows that such technologies as ceramics, the smelting of iron and copper, and weaving with a loom were discovered independently in several world regions, including Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Eurasia. It is also available on Kindle, currently at the price of $15.37, and reads most easily in Kindle´s Cloud Reader.

This book offers a new way of understanding not only African history but also world history.

AfricaFocus Notes is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Here are a few excerpts from Chapter Two of Ehret´s new book.

African Firsts in the History of Technology

Africans living in the heart of the African continent participated separately and independently in the key technological transitions of ancient world history. And they did so during the same broad eras as peoples in other parts of the globe. In at least two instances, Africans appear to have brought notable technological innovations into being, not only just as early, but even earlier, than did people living anywhere else in the world.

...

Two primary, very long-term trendlines of technological descent lead from ancient times down to the more complex technologies of later ages. One line we might characterize as chemical, and the other as mechanical. Each line of development began separately in more than one part of the world, among both Africans and peoples of other continents.

Ceramic Technology in World and African History

The earliest in historical time of these lines of descent in technological innovation took shape with a new development in human mastery of chemical processes—specifically, the multiple, independent inventions of ceramic technology in several distantly separated parts of the world. Ceramic technology was a major transitional development in our mastery of the world around us, not only because it is the earliest sophisticated pyrotechnology—that is to say, the earliest formal technology using heat to remake the chemistry and therefore the usefulness of earthen matter—but because of the long-term historical ramifications of that discovery.

Ceramic technology was of major significance, initially, because of its contribution to human food preparation and hence its potential effects on human health and human population growth. In the subsequent eras of world and African history, ceramic wares often became valued commodities, contributing to the growth of both short- and long-distance commercial enterprise. But what we often may fail to fully appreciate is the foundational place of ceramic technology in the chains of invention that lead down to the technological world of today.

...

The very first invention of ceramics did not take place in Africa but rather in East Asia. Recent discoveries place the beginnings of this development at around 18,000 BCE in areas around the Yangtze valley of China. By around 14,500-12,000 BCE, peoples living across a second set of East Asian lands had begun also to produce pottery, with their earliest known wares found at sites in the Amur River region, more than 1,500 kilometers north of the Yangtze valley, with a subsequent spread of pottery making to Japan. During this period, by the way, because of the lowered ocean levels of the Ice Age, Sakhalin, along with what are today the islands of Japan, formed a peninsula extending south from the lower Amur region of the Asian mainland, one that may at times have also connected to the Asian mainland at the south through Korea. ...

Across the wide expanse of lands between the Yangtze and the Amur River regions, however, the earliest pottery yet known is still later in time, so the more northerly East Asian ceramic development seems likely to have been independent of the Yangtze invention of this technology and therefore to have been the second-earliest such invention in world history, rather than the result of a technological diffusion from the south.

But it was Africans who brought into being the third-earliest invention of ceramics. Where did that development take place? People living in western Africa—12,000 kilometers distant from the Yangtze region—independently created this technology. By no later than 11,500 years ago, around 9500 BCE, Africans living in what is today the country of Mali were fashioning pottery. The geographical region of this invention lay in the areas south of the great bend of the Niger River. These lands fell within the areas where the proto-Niger-Congo language would have been spoken and thus where the Niger-Congo language family originated. The earliest ceramic inventors of Africa, and third-earliest inventors of ceramic technology in the world, spoke early languages, we believe, of that language family. ...

What is more, not just the third-earliest, but also the fourth-earliest invention of ceramic technology in the world took place three millennia before the appearance of ceramics in the Middle East, and four millennia before this technology began to spread from the Middle East westward to the eastern parts of Europe.

People living 3,000 kilometers east of Mali, in the southern half of the eastern Sahara, began to fashion ceramic ware almost as early, during the ninth and eighth millennia BCE . This second African creation of ceramic technology, as our knowledge now stands, is not attributable to diffusion from the West African center of invention. Everywhere, this second tradition occurs in regions where people have for millennia spoken, not Niger-Congo languages, but languages of a second major African language family, Nilo-Saharan. ...

Women as Inventors and Innovators

The origins of ceramic technology in Africa alert us to something else of historical significance—something of great general importance for historians of early world history everywhere, namely, its gendered aspect.

Women, it appears, were the inventors, the tinkerers, the technological experimenters who created both of the two early African ceramic traditions. The comparative cultural evidence right across the continent strongly supports this inference. Everywhere—except for a very few areas where, in recent centuries, men were able to take over the roles of commercial pottery producers—women have long been the makers of ceramic wares and, often, the guardians not only of the knowledge and practices, but of special rituals meant to ensure the success of their work. ...

For peoples outside Africa, the past five to six thousand years of patriarchal dominance right through the whole middle belt of the Eurasian landmass have left historians and the general public with the often-unacknowledged presumption of male agency in technological advance. The history of ceramic manufacture in Africa should stand as a great corrective to that presumption, a corrective to how we think about women and men in history. ...

Metallurgy in Ancient Africa

But ceramic production was not the only area of early African technological invention. A second major line of early technological advance in ancient world history, fundamental for modern technology, grew out the foundational pyrotechnology of early ceramic production. People in several different parts of the world independently brought metallurgy into existence as a second transformative technology of the ancient eras.

It is surely not accidental that each separate region of the world with early smelting of metals from ores was a region where ceramic technology had previously been established. Possession of ceramic technology meant that people in those regions were already well acquainted with the capacities of fire to change the chemical composition of earthen matter. Metallurgy expanded this understanding of the application of fire to the processing of earthen material, but in a new way. It applied fire and heat not to reshape the chemistry of earthen matter as it was constituted in nature but rather to break that matter down chemically—to separate out parts of such matter and then to form the extracted material into new kinds of cultural items.

As with ceramic technology, the development of metallurgical techniques took place separately in multiple parts of the world. And once again Africans living in the heart of the continent separately initiated this kind of advance. In different parts of the world, copper tended to become the most important of the early metals to be exploited because of its malleability into objects and perhaps for another reason: its melting point, 1,085° C, falls in the same ranges as the temperatures often generated in the baking of early ceramic wares.

What is actually most arresting about African metallurgical history is the continent's special place in the history of iron metallurgy worldwide. In the versions of the histories that used to be taught, and which are commonly still being taught, iron metallurgy had a single beginning in Anatolia around or before the middle second millennium BCE. According to this understanding, within a few centuries this technology began to diffuse outward from that region to the rest of the world, spreading first to the rest of the Levant and the Middle East between 1300 and 1000 BCE and, from there, eastward to India and subsequently also westward toward Europe.

This technology, it was supposed, then passed from southern Arabia across the Red Sea to the Ethiopian Highlands by or before the mid-first millennium BCE. Farther west, in North Africa, the Phoenicians introduced iron at their settlement at Carthage in the late ninth century BCE. Ironworking spread, in addition, by or before the fifth century BCE, to Meroé, either south via Egypt or across the Red Sea from Arabia, with Meroé thereafter becoming a major new iron-producing center.

The conventional assumption used to be that iron then subsequently spread from these introductions along the northern fringe of Africa and southward to the rest of the continent. But that view fails in striking fashion to explain the history of ironworking farther south in Africa, south of the Sahara. Already by 1000 to 700 BCE, even before the Phoenician settlement at Carthage, ironworking was well established, not only more than 1,500 kilometers farther south in Africa, but at locales extending from east to west across the African savannas. The farthest west of these sites, dating to the eighth or ninth century BCE, were in the lands of the Nok culture of north-central Nigeria. Other sites dating as early have been found in the nearby southwestern Chad basin. And far away to the east, in Rwanda, the archaeologist Marie-Claude Van Grunderbeek and her team excavated smelting furnaces dating to as early as the mid-eighth century BCE. Africans living well south into the African continent, as this chronological evidence shows conclusively, must have independently invented ironworking.

Part II: Other Books Worth Noting

Earlier this year, in March, I cited On the Origins of Human Speech and Language (2021), by George Poulos, in AfricaFocus at https://africafocus.substack.com/p/world-music-is-african-music. It is not available on Bookshop.org, but is available from Kindle.

Before European Hegemony

Origin Africa: A Natural History (July 2023) is a fascinating account by biogeographer Jonathan Kingdon. Kingdon was born and grew up in Tanganyika, where his father was a colonial district officer who rotated to a different district every two years. The book is both a memoir and an account of the continent, from its origin in the shifting of tectonic plates, with the southern hemisphere of Gondwanaland splitting into west (South America), central (Africa) and east (Australia). The author then moves through an account of the evolution of life, including primates and human beings in particular.

Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 (1989), by Janet Abu-Lughod, is a book that I have long intended to read because of its intriguing title. I was able to buy a used copy recently, and started to read it. It is very thought-provoking and well-researched. Abu-Lughod builds, as the title suggests, on the work of Immanuel Wallerstein, but does not hesitate to amend some of his premises.

Five and a Half Centuries of Global Apartheid

In Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War, Howard French eloquently weaves his journalistic travels into a paradigm-shifting historical account. Instead of beginning with the transatlantic voyage by Columbus or the European quest for a new route to Asia, French links the origins of European domination and the transatlantic slave trade to Portuguese efforts to bypass Muslim control of the gold trade across the Sahara between mines in West Africa and Europe, with the byproduct of the slave trade from Sāo Tomé to the Akan states in what is now Ghana.

Ana Lucia Araujo, a Brazilian scholar based at Howard University, author of Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History (2017, with a new expanded edition coming at the end of November 2023), is one of the leading historians of slavery and the slave trade in the Atlantic world. Her work is built on extensive research in multiple languages as well as prolific and coherent publications and other presentations of her work. See https://analuciaaraujo.org/ for much additional background.

In Not a Nation of Immigrants: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion (2021), Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz provides an overview of the history of the United States that convincingly demolishes the misleading mythology propagated by John F. Kennedy in his book Nation of Immigrants, first published in 1958. Dunbar-Ortiz presents a far more complex narrative including conquest of indigenous peoples by settlers and of territory taken by war from Mexico, the violent import of enslaved peoples of African descent, and subsequent waves of immigration incorporated into a society already structured in a racial hierarchy.

In Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (2019), Adom Getachew recasts the understanding of the goals of Black Atlantic anti-colonial movements as including not only national independence but also the fundamental reordering of the world order. Seeking to create an egalitarian post-imperial world, they attempted to transcend legal, political, and economic hierarchies by securing a right to self-determination within the newly founded United Nations, constituting regional federations in Africa and the Caribbean, and creating the New International Economic Order.

Harsha Walia, in Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism (2021) lays out a superb analysis of how control of migration is fundamental to maintaining the current order of global inequality along lines of gender, class, race, and national origin.The book includes a foreword from renowned scholar Robin D. G. Kelley and an afterword from acclaimed activist-academic Nick Estes.

The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions (2021), by Chuck Collins, provides a detailed analysis of how the system of concentration of wealth works. Collins draws on his experience both as an heir of great wealth himself and on his work as director of the Inequality Project of the Institute of Policy Studies, which produces a steady flow of research studies, commentaries, and policy initiatives.

For additional shorter notes, not sent out by email, but available on the web, visit https://africafocus.substack.com/notes.

Very interesting!The fact that I haven´even been able to read all the reviews says something about all that I am doing right now.This not being retired any more is very time comsuming. And I will soon begin decorating the ¨Museo de las Orquídeas ¨that Juan and his partner are opeing behind the Sombra del Sabino the end of November. I have to put things for orchids etc without spending ANY money which is very challeging.